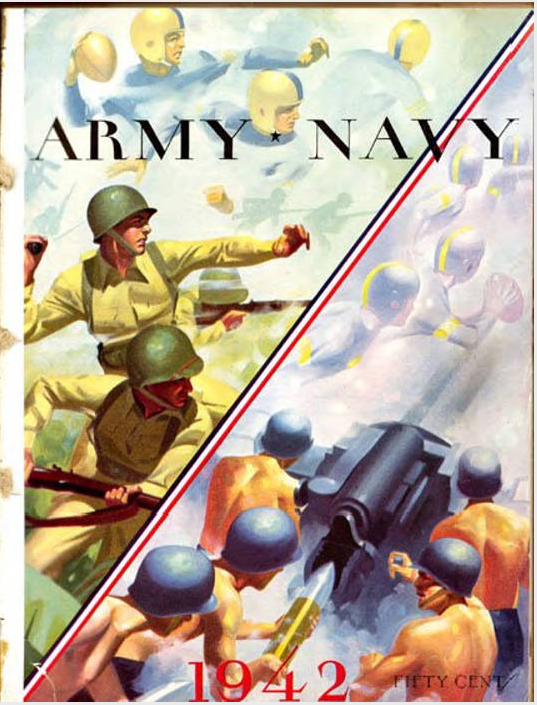

In November 1942, wartime travel restrictions impacted the Army-Navy Game and resulted in a surreal football game played in a half-empty stadium on the shores of Spa Creek.

On Saturday, November 29, 1941, 98,497 football fans watched Navy defeat Army 14-6, at Municipal Stadium in Philadelphia. As the game was being played, the Japanese fleet was secretly steaming toward the Hawaiian Islands. Eight days after the Navy win, on the afternoon of Sunday, December 7, the team was back in Annapolis, being feted at the home of the Naval Academy superintendent.

Navy had finished the season 7-1-1 with the #10 national ranking. In mid-afternoon, the superintendent was called to the telephone for an urgent message from Washington. "When he came back into the room his face was ashen," Bob Woods, one of the players, later told The New York Times. He closed the doors of the big ballroom and said: 'Gentlemen, we are at war. Return to your quarters.' "

When the Midshipmen reached Bancroft Hall, the Marine detachment there had strapped on pistols. A year later, World War II had erased many traces of normalcy in United States but college football was still being played and Army and Navy continued to field strong teams. As the season unfolded, some questioned whether the 1942 Army-Navy game should take place at all, out of respect for those in harm’s way and in light of the gasoline rationing and other travel restrictions.

President Roosevelt, believing the game was important for morale, intervened and suggested that the 1942 game be played in Annapolis, at Thompson Stadium, on the Navy campus. It would be radio broadcast around the world.

Not far from the superintendent’s residence, Thompson Stadium sat on the edge of Spa Creek, on the present site of Lejune Hall swimming complex. The 12,000-seat stadium was completed in 1912. According to Naval Academy lore it was built with steel originally intended to construct war ships but diverted to the academy to serve as the foundations of the grandstands. The Hell Point neighborhood, a ferry dock at the foot of King George Street, and the J.F. Johnson Lumberyard were alongside the stadium, in the shadow of the grandstand built of battleship steel.

Officials conferred and it was decided that the game would go on with heavy restrictions on ticketing. No one living outside a 10-mile circle around the Maryland State House would be permitted to attend. The only exceptions were Academy employees, girlfriends of midshipmen, and a limited number of press. Those who received tickets were required to sign a form stating that they lived inside the radius and that they would not resell the tickets.

In early November, Roosevelt signed a measure lowering the minimum draft age from 21 to 18. A week later, Annapolis had its first daylight air raid drill. As the war ramped up, scrap metal collection was imperative and piano sellers advertised free haul away and recycling for patriots willing to donate their piano to the war effort (“Two and one half 500-ton bombs can be made from the salvage metal in an ordinary piano.”). So serious was the local metal collecting effort that the Elks Club placed a box along Main Street for recycling of old keys.

Across Spa Creek from the Academy, the Annapolis Yacht Yard employed nearly 500 workers who worked three shifts building wooden PT boats and minesweepers. The famous old schooner America sat smashed and uncovered at the yard, silently awaiting her sad fate. Just across the Severn, the mysterious Robert Goddard was testing “Jet-Assisted Take Off.” In the late summer and early fall of 1942, his team strapped rocket engines to a Catalina Flying Boat and tested it on the river.

Despite this war effort all around, “Army-Navy” would be played and there was football business to attend to. As game day approached, the underdog Navy team practiced along the shores of the Severn with canvas walls stretched along the sidelines to ensure secrecy. “Jimmy”, a stand-in Army mule was secured from a farm just outside of Annapolis and was set to patrol the Cadet sidelines. The night before the game a Navy pep rally was held on Farragut Field but no bonfire was lit due to wood rationing.

The day of the game brought equally surreal scenes to the Annapolis waterfront. Representatives from the federal Office of Price Administration, charged with enforcing rationing, inspected cars in the vicinity of the stadium to ensure none had improperly carried fans to Annapolis. Inside Thompson Stadium, half of the Brigade of Midshipmen was ordered to cheer for Army and they took instruction from cheer books sent down from West Point. These cheer books featured humorous illustrations of a goats braying like mules and cartoons of midshipmen cheering with fingers crossed.

On November 28, 1942, the Army-Navy game was played in Annapolis for the first time since 1893. The stadium was less than full and Navy won 14-0. The game has not been played in Annapolis since.

About the Author: Dave Gendell is the co-founder of SpinSheet Magazine. He lives in Annapolis. Contact him at [email protected].