A sailboat that has done real things

There’s an odd and sometimes hard calculus that stems from working on a sailboat that has done things—real things—in her past. My boat, Ave Del Mar, is one of those boats. A 1967 Rawson 30 cutter, she has, among other things, circled the globe, transited the Suez and Panama canals, rounded Cape Horn, been dismasted in a hurricane, lost a bowsprit in Patagonia, and collided with an Alaskan fishing vessel at sea.

The work that I had to do to Ave when she became mine in the spring of 2013 was overwhelming to me despite my general competence and despite the relative simplicity of its scope. I didn’t come from the boating world, never attended sailing camp, and knew what little I knew about boats from reading “10,000 Leagues Under The Sea” and taking a couple of vacations to visit my friends on their Island Packet.

I replaced corroded fuse blocks with shiny circuit breakers. Incandescent lights fell away to make room for efficient LEDs. The bottom got a good fresh paint job and the engine an oil change. It was all logical, all relatively easy. When the work was completed to my satisfaction, I headed south.

Ave and I crept down the Intracoastal to Florida, learning as we went. I spoke on the phone regularly with her former owner and now friend of mine Jamie Bryson, devouring all the advice I could get and always hoping for evidence of his approval. I sailed his boat his way, the best I could, with sprinkles of influence from time on my friends’ IPY tossed in like vaguely remembered math formulas from high school. I was a living stand-in.

We learned each other's ways

Slowly Ave and I learned each other’s ways, slowly I learned how to sail, and slowly she became my boat. I stayed humble, never sailing too far beyond my means and always staying on the conservative path.

South and east through the Bahamas we went, down the Windward Passage to Haiti, and west to the sunny, music-filled shores of Port Antonio, Jamaica. Problems crept into my life the way cold creeps into your bones in the deep of winter. The black-iron fuel tanks were starting to decompose. The tiller pilot died. Twice, winches flew airborne from their bases while under load. Sails were deteriorating, and sail tape could only do so much. The boat needed attention and so did my bank account, so I made the decision to point north and come home to take care of business, mine and hers.

Winterized, she sat on the hard just two slots removed from where I found her all those years prior. I retreated to the city to work on refilling the sailing kitty, and when I returned a year later, I found that the dynamic had changed. I was no longer working on someone else’s boat, dancing someone else’s moves. Ave was mine now, the work was mine, and the parts that held her together were mine, too.

A clear November afternoon found me in that boatyard in Virginia’s northern neck, holding Ave’s old stuffing box hose in my hands, asking Charlie, the yard manager, if he could order me a replacement piece.

“Sure,” he replied, “but that’s the wrong kind of hose. That’s just a water hose. Definitely not a safe way to go.”

I stared at the hose in my hand. It was on the boat when I bought her, and it had been on her as she sailed tens of thousands of open-ocean miles. Jamie had died a few years earlier, but he had been a boating genius and had made incredible improvements to the little boat I now called mine, making her a sturdier, safer bluewater vessel. I found it difficult to accept that he would have endangered his beloved world-traveler with a sub-par component, but there it was. I was perplexed.

There had been other head scratchers as well, repairs that didn’t make sense to me. I have never had a part fail on a long ocean crossing, have never had to make a repair in big, rolling seas. But as my experience grew aboard the boat that was now mine, so too did my freedom to look at a mystery and say to the skies above, “Jamie—what the hell?”

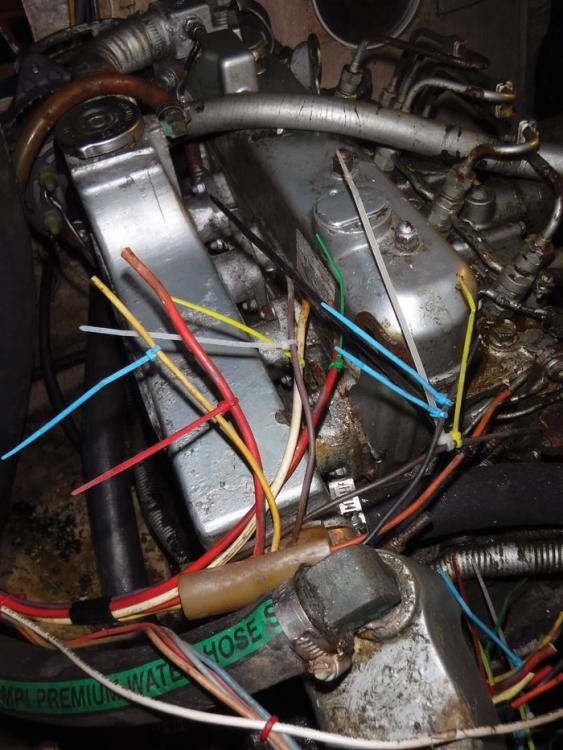

My greatest challenge coming back to Ave after her year of respite was a battery bank that simply refused to hold a charge. Something was draining the batteries with an alarming efficiency. Day after day I chased wires, multimeter in hand, cleaning connections and taking resistance readings. I replaced the starter and rewired the voltage regulator. But somewhere in the engine compartment something was awry. As potential electrical leaks were ruled out one by one, I decided to trace the entirety of the wiring harness from the gauges backwards, working up the electrical stream.

It didn’t take long for the meter to report an open line. I crawled deeper into the engine compartment, tracing the suspect harness as I went. As it curled around out of view under the exhaust elbow hose, my fingers found an odd clumping of tape—old, brittle duct tape. I cut away the zip ties that held it in place and pulled the harness out into the open.

Slowly and full of anticipation I unrolled the loops of tape, hoping the answers to my charging issues were hidden within. The harness was odd and lumpy in my hands. Colors soon began to emerge—bright oranges, blues, and yellows—as the tape fell away. And then I saw my problem: someone had spliced a new wiring harness to the old one with, of all things, wire nuts. It had been taped off and shoved out of the way, never to be seen again.

A shift began to happen

Jamie had accomplished so much more aboard Ave Del Mar than I could ever hope to, but this chilly fall day on his former boat in a small boatyard in Reedville, VA, we spoke again, as I looked upwards towards the heavens and asked him what, exactly, he had been thinking.

The harness splice was easy enough to repair, and the charging issues were soon resolved. I avoided falling into judgment over the mess I had found, avoided with every ounce of my being the temptation to lay blame at anyone’s feet. There was a shift in the dynamic between me and Ave’s erstwhile owner. I wasn’t him and didn’t have the experience he had, but I was no longer the naïve, starry-eyed buyer, afraid to have opinions on the storied vessel that was now mine.

I will never have the chance to sit down with Jamie and get answers to this or any other question. We had a fantastic relationship after I bought his boat, speaking often and sharing successes and failures as they came my way. He was without question my biggest cheerleader.

The shift that had happened was good, not bad. He had taught me well—well enough that I gained confidence and a voice. Well enough that I can question the things that should be questioned. Well enough that I think he would respect me even more if I could sit him down and ask, simply, “Jamie, what were you thinking?”

Then I would listen to his reply and probably learn even more.

By John Herlig