The striking Seven Foot Knoll Lighthouse is part of Historic Ships in Baltimore and available for tours. The former keeper’s dwelling now contains historical exhibits on the building of the light, as well as other lighthouses on the Chesapeake Bay, and from the balcony guests can enjoy a wonderful view of the Baltimore Harbor. Click here for information to plan your visit.

Early Years

On March 3, 1851, Congress appropriated $17,000 for a lighthouse to be erected on Seven Foot Knoll in the mouth of the Patapsco River. The Lighthouse Board recommended the structure should be a screwpile lighthouse (the first screwpile lighthouse was only just built in 1850 in Delaware Bay) and that it would replace Bodkin Island Lighthouse, built in 1822.

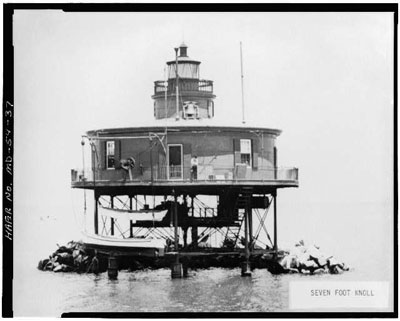

From the outset there were differences in opinion regarding how the lighthouse should be built, causing the contract for the project to expire before work could really begin. On August 3, 1854, funds of more than $34,000 were re-appropriated, and the screwpile lighthouse was completed in 1855. The one-story circular structure, bordered by a gallery deck, rested atop nine iron screwpiles. Above the dwelling is a 15-foot diameter watchroom, and above that the lantern room encircled by a deck.

The Seven Foot Knoll light was one of the first lighthouses to use pre-fabricated parts, which allowed certain pieces to be transported to the station and quickly assembled. The lantern room featured a fourth order Fresnel lens, which produced a fixed white light and a fog bell. The light first shone on January 10, 1856.

In January of 1884, ice floes dislodged one of the lighthouse’s iron pilings causing its keepers to evacuate to safety. To try and prevent such damage from reoccurring, 150 piles in groups of 10 were placed in a circle around the structure, but by 1894 it is reported that “all the clusters of oak piles placed around the lighthouse had disappeared.” Later riprap was placed at the base of the lighthouse to try and deflect damage from future ice. But these were only temporary fixes.

The light is automated

In 1948, after more than 130 years of manned operation, Seven Foot Knoll Lighthouse was automated. Prior to this, a few families actually made the lighthouse their home. Historic Ships in Baltimore recounts the story of Eva Marie Bowling who was born at the lighthouse in 1875, and nicknamed “Knollie” after her birthplace. Her father, James T. Bowling, served as keeper of the light from 1874 to 1879. The family had an abundance of seafood and would use that to trade for vegetables from local farmers. They also had a hog pen and chicken yard on the platform below the living area. When foul weather hit, the livestock were temporarily brought inside with the family. By the late 19th century however, increased regulation within the Lighthouse Service effectively put an end to families living at Seven Foot Knoll.

Years later when the light became automated, it began to fall into disrepair with no one to regularly maintain the structure. It was declared “excess property” by the Coast Guard in 1969 and donated to the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, VA, but the museum gave up its claim in 1975. Inspections in the 80s described the lighthouse’s condition as “grim,” due to its deteriorating iron legs. The structure was also covered by graffiti.

It seemed that the Seven Foot Knoll lighthouse, only one of two screwpile lighthouses on the Chesapeake still in its original location, would have to be demolished. But the City of Baltimore intervened to have the lighthouse moved to Pier 5 as part of a redevelopment plan for the Inner Harbor. In October 1988, the 200-ton lighthouse was severed from its iron pilings and lifted off its foundation by a massive crane. It was then brought by barge up the Patapsco River to its new home.