Sailing the Ocean as a Family Affair

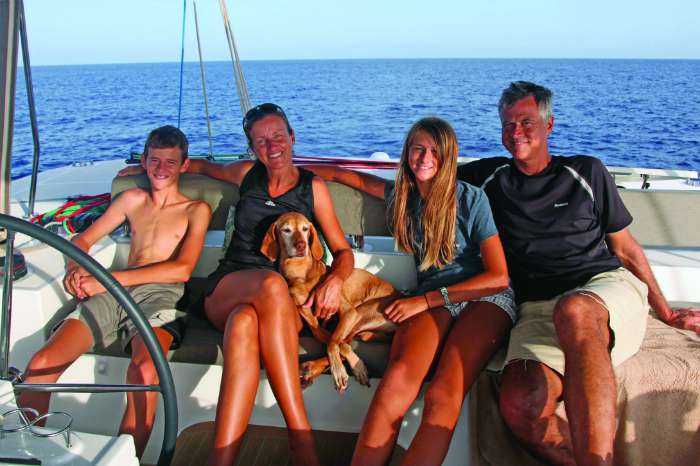

As a family we had always loved the ocean, but we never dreamed we would be crossing one together. In the summer of 2015, my wife, Valerie, and I finally made good on a promise to ourselves, and we took our two children, Madeleine, 12, and William, 10, on an extended family cruise on our Lagoon 450 Sacre Bleu. After a year exploring the Mediterranean, we were in Gibraltar looking west, pondering the seemingly infinite Atlantic Ocean.

The cruising we had been doing up to this point along the European coast was relatively easy. For that year, we were never far from a safe harbor, a cell phone signal, or a grocery store. We always had a current weather forecast, and we never ventured offshore long enough to be too surprised by a change in conditions. The transatlantic was going to be very different. A reliable forecast is good for three, maybe four days, and it takes three weeks to cross the Atlantic Ocean. Once we were beyond that forecast window, we were at the mercy of whatever appeared on the horizon. There was no safe harbor.

First-time ocean crossers frequently join a rally organized by a team of veteran sailors. As a flotilla staging in one location, crews spend time together educating themselves, comparing notes, and helping each other get boat and crew prepared for what is considered the final exam of cruising. The rally organizers play an important role giving seminars, advice on provisioning, inspecting boats for safety, and generally instilling confidence in the skippers and crews. They provide this service on both sides of the ocean but leave the participants to do the crossing on their own. Veteran sailor and author Jimmy Cornell had an organized rally, the Atlantic Odyssey, leaving from Tenerife, Canary Islands, in two weeks’ time. It seemed the ideal opportunity for us to take on our first ocean crossing with a little help from the experts, so we signed up.

Our marine insurance company required a third adult watch onboard for the transatlantic. With the help of a web-based service that matched crew with boats, we arranged to meet our new crew member in Gibraltar. We had to get ourselves from Gibraltar to Tenerife, where the rally started, and that required sailing a stretch of over 700 miles of open ocean. Since we were going to do this first leg by ourselves, I used a weather routing service to help us plan the trip. After providing my itinerary and time window to the service, I was put in touch directly with one of their routers, who provided excellent guidance on when to leave, what route to follow, and what weather to expect. The run lasted three and a half days, and the highlight of the trip came at day two, when the sunrise revealed that we were being followed by a 40-ton fin whale. As big as the boat, the creature swam just a few feet off our starboard for 20 minutes and then puffed a warm cloud of mist and vanished into the deep.

Once in Tenerife, we began a week of preparation that included daily seminars covering medical emergencies, storm preparedness, improvising repairs, satellite phone use, provisioning, and more. Twenty-three sailboats from 12 countries had convened in Tenerife for the crossing. Many of the boats were crewed by families, some with kids close to our two children’s age and some even younger. The Odyssey sent staff to inspect each boat and review a checklist of safety gear and electronics that were a requirement to participate in the rally, including a satellite phone, which we rented.

With provisioning and meal planning done, maintenance on the engines performed, fuel and water tanks filled, emergency water jugs loaded, first aid kit inventoried, spare parts packed, and software updated, the boat was ready. More difficult was getting our lives ready for dropping out of civilization for three weeks or more. Bills had to be paid, emails sent, social media posted, and a last call made to family members.

The rally organizers set up a starting line just outside the mouth of the harbor, with all 23 boats departing within 15 minutes of each other. The first day, most of the boats stayed in visual contact; the next morning we were completely alone. The fleet had literally scattered to the wind.

Each day at noon, GMT, we connected to the satellite and downloaded the weather forecast from NOAA consisting of a synoptic chart and a text-based weather synopsis. The synoptic chart is a simple representation of wind speed and direction and atmospheric pressure—enough information to provide a reasonable picture of the weather we could expect in our part of the North Atlantic.

We settled into a routine that would not change for the three weeks of the crossing. We were three adults, and each of us took four-hour watches after dark. During daylight hours we did not keep a formal watch and even let our two kids sail the boat. Breakfast and lunch were do-it-yourself affairs, while dinners remained coordinated, sit-down events. Valerie did most of the cooking, not so much out of old-fashioned tradition, but because she had created the meal plan and provisioned accordingly. After dinner, the boat shifted to a night routine, with the adults at the helm and the kids inside until the sun rose the next day, when we would start it all over again.

Sailing the boat was usually an easy, one-person job. The temperatures for the entire voyage were mild, even at night, and we rarely needed any covering beyond a T-shirt and shorts. Standing watch involved keeping an eye out for other boats and making sure the sails were correctly trimmed. Boat traffic was nonexistent. As for sail trim, since we were always sailing dead downwind, when the wind shifted, rather than trimming sails we would alter course slightly. We encountered rough weather in the first couple of days of the crossing, with winds peaking at 30 knots, and a few squalls as we approached the Caribbean. Otherwise, the wind measured a steady 15 and 20 knots and always behind us. The synoptic charts we downloaded daily never brought us a weather report that concerned us. We could credit this good fortune partly to luck and partly to timing: The rally began in mid-November, just after the end of hurricane season.

On day 19, just as I was taking the 4 a.m. watch from Valerie, the lights of Bridgetown, Barbados, rose up from the horizon. We were all exhausted, proud, and a little melancholy about it all being over. Part of me had expected more of an adventure, and the other part of me was relieved by the monotony of the trip. Madeleine and William—now 14 and 12 years old—had an achievement in their young lives that few would ever attain, and we hoped the perspective they gained from crossing an ocean will make other ambitions seem more achievable. After a year of cruising, through storms and anchor draggings, deck swabbing and night watches, we were a crew and a family, and we would always be bound by the memories of crossing an ocean together.

About the Author: Jim Toomey is an internationally published humor writer and syndicated cartoonist best known as the creator of the popular comic strip Sherman’s Lagoon, published daily in over 150 newspapers. In 2015, his wife, Valerie, talked him into buying a sailboat and going to sea with their two kids and the family dog, and he subsequently wrote a travel memoir about the voyage called “Family Afloat.”

M Yacht Services has been the longtime sponsor of our Bluewater Dreaming column.