Expecting the Unexpected, Boat Prep, and Keeping Your Cool

An experienced bluewater sailor shares his knowledge on expecting the unexpected, smart spending on boat prep, and staying calm in heavy weather.

For this installment of our offshore series we checked in with veteran offshore skipper Bob Fox, who campaigns his XP 44 Sly out of Annapolis, MD. For many years Bay sailors knew Fox as the owner of the highly competitive J/42 Schematic, but last year, shortly before the Annapolis to Bermuda race in June, Fox purchased Sly (formerly Rival) from local sailor and competitive offshore racer Bob Cantwell. Fox is a member of the Annapolis Yacht Club and the Storm Trysail Club, whose membership is by invitation only to expert offshore sailors who have experienced storm conditions and are capable of commanding a sailing vessel in such conditions.

Fox’s sailing resume boasts thousands of offshore miles, most of them racing. Early on he held crew positions on Jim Rogers’s Swan 47 Panther and Mark Myers’s Swan 51 Tonic, and he says crewing for very experienced offshore skippers was a good way to learn and build confidence and make the leap to sailing his own boat in bluewater. As an owner-skipper, Fox has logged five passages to Bermuda (twice from Newport and three times from Annapolis; last summer was the first on Sly), and six trips from Annapolis to Newport (all aboard Schematic). This year he is planning for the 2019 Annapolis to Newport Race aboard Sly.

Crew Is Crucial

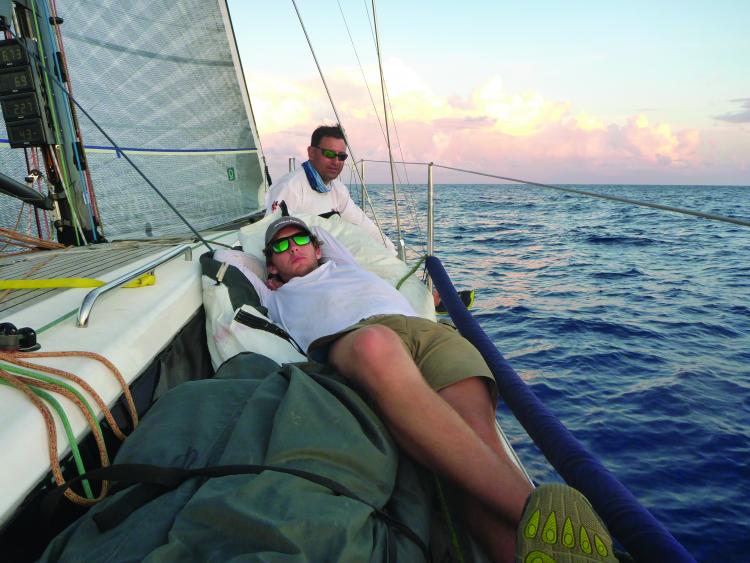

Offshore sailing always brings the unexpected. A competent, cordial crew goes a long way to handling the inevitable dicey moments. When a harsh wind kicks up suddenly or seasickness rears its ugly head, trust counts. Conversely, if the doldrums set in, a group that’s willing to make the best of the situation will keep everyone’s spirits up.

Compatibility is important, but an offshore crew has got to also be self-sufficient and resourceful—your lives literally depend on each other. Fox and other successful offshore leaders manage to fill their boats with groups of good people who have compatible personalities and also bring knowledge and complimentary skill sets to the boat. “I’m very fortunate to have a great crew that chips in and helps prepare everything for the race,” he says.

“It’s also a good idea to have a few extra crew as back up,” he adds, “because once in a while someone can’t commit for one reason or another. I would also strongly recommend having aboard crew with significant offshore experience. My navigator, Greg Dupier, is a wiz. He has considerable experience and an excellent track record; he knows the technology, weather, science, math, and geometry behind sailing. Whenever Greg’s onboard, the boat does well.

Feeding the crew with food that is filling, nutritious, and easy to handle is one key to a pleasant offshore experience. A competent sailor who can bring some culinary skills to the boat will always be a sought-after crewmember. Never underestimate the importance of feeding your crew well. Ocean-going captains tell us all the time that keeping the team well fueled is one of the primary responsibilities of the person in charge.

Fox is fortunate to have crew members that willingly take on this important role. “We have great meals during the race; I’m constantly amazed. A couple of my crew, David Banks and Warren Dahlstrom, are borderline gourmet cooks, and they relish the opportunity to do the cooking,” he says. “They handle all the provisioning and cook and freeze dishes before we leave. We are all very grateful for their efforts. It makes for a happy crew. But I do like peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, too.”

A Well-Prepared Boat

The transition from inland coastal cruising to offshore passagemaking isn’t for the faint of heart. The leap usually requires additional equipment not needed for Bay cruising or daytime racing. Racing requires the boat meet a long list of safety requirements, including a life raft, alternate steering, AIS, updated electronics, man overboard module, the ditch bag, harnesses, jacklines and clips, and the list goes on.

“Don’t let it be overwhelming or discouraging; there are plenty of other sailors and clubs who are willing to help out. You can tell when you look at boats that they are prepared to go offshore; don’t be afraid to ask questions. Most are happy to offer helpful advice and a good story or two.”

Even for those who’ve sailed offshore for years, each season means re-examining the hull, rigging, and safety gear. Fox explains, “At the start of every year, we crawl through the boat looking for things of concern—rust on shackles, hairline cracks, anything of that nature. For racers like myself, you’ve also got to keep current and up-to-date on race regulation requirements and certifications for all the safety equipment. We check and double check everything. We are always thinking about what could be the next thing to go wrong.”

We’ve heard this from seasoned skippers before: don’t rush and don’t be cheap; you’ll thank yourself if things go sideways far away from help. Fox says, “I don’t ever want to be in a situation where someone gets hurt or even worse, because I was trying to save a few bucks; keep the boat and gear in good shape. When the weather kicks up, this will give you confidence. Prepare for the worst and hope for the best. If you’re prepared to beat in 25 knots and you get a nice reach instead, it will be just that much better.”

Heavy weather is something most sailors fear, and with good reason. “Be prepared. When things go bad, it can be total mayhem. Expect to have a few ‘Oh, #&*!@’ moments,” says Fox, who has experienced winds in the 45- to 50-knot range. “Experience counts. If you’ve got a good, competent crew, they’ll be watching out for the boat and each other.”

Sometimes the unexpected hits full force. Fox recalls this particularly challenging situation: “It was a relatively calm, beautiful night. The water was flat, and we had the spinnaker up. Then, the breeze began to build. It kept building, climbing over about 20 minutes, to 30 knots. I was thinking we needed to get the chute down, and it was quickly gusting to over 40. The night was completely black except for the blinding bolts of lightning. Waves were building quickly, and one came under the boat as we got a gust of wind. The boat began to round up, and I had no helm to steer. All hell broke loose in a matter of seconds. Suddenly we did a Chinese gybe. With a few seconds of warning, and lots of shouting to get heads down, the boom flew across the cockpit. A young crewmember (my son) was pinned against the cockpit with the mainsheet. The spinnaker was flailing.” In this instance, Fox’s capable crew recovered quickly, and no one was hurt.

Preparation was key. “Practice lots of sail changes. Everyone needs to be comfortable with the rigging, how it lies, and how it’s used,” says Fox. “A good understanding of what the boat can do is really important. When a boat gets loaded up in heavy conditions, you’ve got to pay more attention to all the systems. On Schematic, because I sailed the boat with the same crew for years, we were very comfortable sailing in 25-30 knots of wind. One person could reef (on) that boat, provided they knew what they were doing. As soon as you start thinking about a reef, it’s the time to reef; the boat can actually be faster because you are in control, and it is much more comfortable and forgiving.”

A chart indicating the range of wind speeds that are appropriate for each sail will be provided by most sailmakers, but real proficiency in sail selection comes from experience and time on the water. Practice in all kinds of weather is the best preparation. And you don’t have to go offshore to get some really good experience. Time and time again we talk to offshore sailors who tell us some of the most extreme conditions they’ve experienced have happened in the Bay. Ideally your sailmaker will help you to understand your options and offer suggestions for different conditions.

With six different headsails, plus a storm sail for 35-plus knots on his new boat Sly, Fox says wind speed is important, but it isn’t the only consideration in his sail selection. “Of great importance are: how well you know the boat and its capabilities and how confident you are in the crew. There have been times when I’ve gone with less sail, even during a race, because I didn’t have my A-team onboard.”

When we spoke with Fox, he had recently read the Review Committee Report on the Fatal Accident Involving Imedi during the 2018 Chicago Yacht Club Race to Mackinac, which had just been issued at the time.

“Reading that report was tough,” he says. “It really made me think. When something goes bad, it can start to multiply quickly and go really bad. I’ve talked to my crew about it. A man overboard (MOB) situation in heavy weather is exponentially more challenging than in calm seas and light wind. We’re going to do a few things differently preparing for this season, including checking our PFD auto inflates and practicing MOB drills in heavy weather.”

It’s 2 a.m., and the only lights in sight are the dim ones from the boat’s instruments. The stars are like a heavenly blanket above, and the opposing watch has quieted down belowdecks. In some ways, night sailing offshore is a little less stressful than it is in the Bay. There’s no shipping channel out there. No shoals. No barges or bridges.

Fox says, “In the past I did not really enjoy the midnight to 4 a.m. watch. In fact, I hated it, but now it’s my favorite. I’ve come to love sailing at night. There is nothing more spectacular than a clear night. When the moon sets with the sun, the Milky Way reflects off the water, and the stars are incredible. You can see satellites moving across the sky. On a cloudy night it’s blacker than black, which I also find awe inspiring. Those kinds of experiences are amazing.”

by Beth Crabtree