Safety Series 2020 Part II: Crew Training

To read a sailing incident report is gut-wrenching: the unexpected events, the small issues that combine to create larger problems, the split-second decisions forced upon skipper and crew. You put yourself in that situation, or you recall your own past brushes with danger, and you realize, no matter how much safety gear you have aboard a boat, if it’s not in proper operating order and the crew doesn’t know where to find it and how to use it, things can go quickly from bad to worse.

Safety at Sea: The “Aha” Moments

The gold standard for safety training is the US Sailing-sanctioned Safety at Sea (SAS) program, which is designed for all types of sailors: racers and cruisers, families and race teams, novices and experts. Safety at Sea includes lectures, written materials, and hands-on training in a controlled environment. In the Chesapeake region we are fortunate to have two SAS courses offered this year (see box on page 37). Heavy weather, man overboard procedures, and communication are just three of the many topics covered. For those who can’t make it to a seminar in-person, the course is also offered online.

Many sailors who participate in the course are surprised that seemingly simple directives and safety procedures they’ve read about in books turn out to be not-so-simple in real life.

“I think the most common ‘aha!’ moment is when participants find out how tricky it can be to board a life raft from the water with full gear on,” observes Chuck Hawley, who is one of the most experienced Safety at Sea moderators, a seasoned offshore sailor, and a nationally recognized speaker on marine safety. “The added bulk of foul weather gear, plus a life jacket, plus water-soaked clothing, makes it very difficult to pull oneself into a raft.

“The second, far less common ‘aha’ moment is when someone’s lifejacket doesn’t inflate after immersion,” says Hawley. “Thankfully, this doesn’t happen often, but even though a person in foul weather gear and clothing is surprisingly buoyant due to trapped air, at least for a while, it’s disconcerting to not have one’s lifejacket inflate. This reinforces one of the key messages of hands-on training: it’s vital to a) maintain one’s life jacket and b) to understand the alternative means of inflating the device.

“A third takeaway, which is related to the second, is the importance of maintaining all of your safety gear. In the 25-plus years that I have been participating in Safety at Sea courses at the Naval Academy, I’ve run into a variety of gear failures since I am generally called on to demonstrate all of the safety gear that’s found on a Navy 44. I should point out that this gear sees more use than would be encountered on the vast majority of recreational boats, and gets better maintenance as well. But I’ve had throw ropes that have been tangled, life rafts that have deployed incorrectly, lights that haven’t lit, and so forth. This reinforces the need to take responsibility for your own gear and not to blame or rely on someone else (except in the case of the life raft, where a factory authorized service center is your best bet.)”

Drill, drill, and drill again

Sure, your crew can expertly throw in a reef on flat water with a steady moderate breeze, but have they given it a go while being tossed about by gusty winds and choppy water? Once your crew becomes comfortable executing safety maneuvers in calm conditions, it’s time to practice with more breeze, choppy seas, and in the dark. It’s one thing to try and retrieve a lifejacket that’s been tossed overboard on a warm, calm day. It’s another thing entirely to try and retrieve a 150-pound object during a dark night while being pelted with rain.

Repeated practice leads to speed and ability, and builds the crew’s confidence that muscle memory will be there when it’s needed. At the end of training sessions, take time to debrief, assess skills, and come up with recommendations for improvement.

Life onboard shouldn’t be a safety concern

Most of us will never encounter an extreme safety emergency, but everyday life aboard can present its own smaller challenges. Give your crew opportunities to become accustomed to life on the slant by spending some extended periods of time living aboard.

Most experienced captains of multi-day passages tell us that their crew performs better, is stronger, has more attention to detail, and gets along better with one another when they have plenty of good, hot meals designed for energy and nutrition. Practice with the gimballed stove, galley belt, and pot restraints. Find the safest way to use a knife (perhaps seated). Learning these skills can go along way toward avoiding injuries. finally, as the galley is one of the most likely places for fire, keep a fire extinguisher nearby.

The more experience your crew has moving around belowdecks while underway, the easier it will become, and not just in the galley. Moving through the cabin they’ll know instinctively where to reach for handholds, and if a crew practices their watch system, they’ll be accustomed to sleeping in a berth on an angle with noise from the rigging, sails, waves, and on-watch crew. Likewise, with time, personal hygiene will become easier, faster, and less messy.

The importance of safety briefings

Once you’ve done your safety education and drills, there might be a temptation to think the crew is good to go, but the importance of safety routine briefings shouldn’t be overlooked. Keeping pre-depature briefings on point will increase the likelihood that the crew’s attention is dialed into what you’re saying.

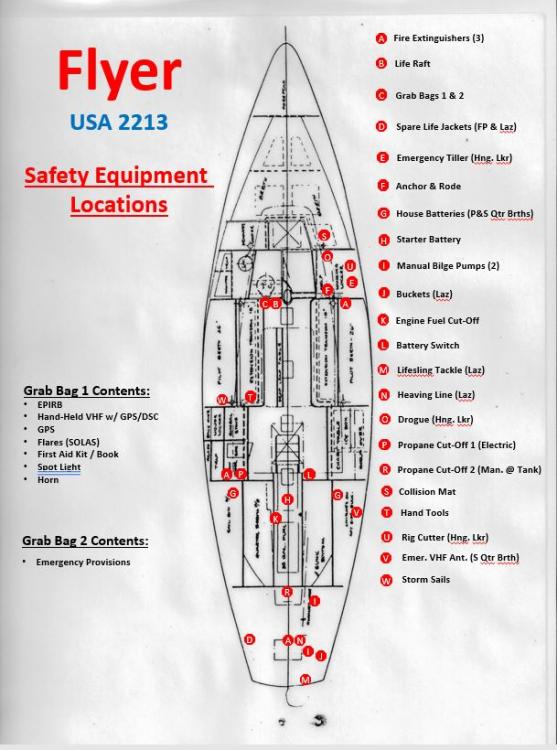

In addition to the “what and where” a safety briefing should stress the importance of teamwork and the necessity of staying calm. Your briefing might include a reminder of the location and use of the most important safety equipment, the location of through-hulls and how to plug them, the location of the first aid kit(s), and any other information you think bears repeating.

With safety, redundancy is good and practice is essential. A foundation of preparedness will enable a crew to think and act quickly if the need arises.

~By Beth Crabtree