Like everyone else, we watched the horrific video of Team Vestas Wind and wondered exactly how that could happen when you have the top sailing talent in the world combined with the best navigational aides available.

An independent report was commissioned by the VOR in December, and was conducted by a panel including Rear Admiral Chris Oxenbould, Stan Honey, and Chuck Hawley. Oxenbould is a former deputy chair of the Australian Navy, Honey won the VOR in 2006 as navigator onboard ABN-AMRO One, and Hawley is the chairman of the U.S. Sailing Safety at Sea committee.

The report itself is a whopping 80 pages long, but we have to admit, it supplied some of the most fascinating reading we've seen in a long, long time. This is a long relay of the information, but we think it's worth reading.

Paragraph 40: The East African Exclusion Zone (EAEZ) "was first established during the 08-09 race in order to minimize the risk from pirates." But over the last three years, the threat from pirates has diminished significantly. 41. "During a briefing at Alicante on 30 September, before the start of the race, competitors were advised of the likelihood that the exclusion zone would be reduced in size shortly before the start of Leg 2 in Cape Town."

43: "On 15 November, a tropical system was forming and was threatening to transit the course. 45: An amended SI was sent out to boats on November 18, replacing the version that was promulgated publicly (and also seen by any potential pirates).

Leg Two, from Cape Town to Abu Dhabi, started on November 19. The new route had "an amended East African Exclusion Zone and now included the Cargados Carajos Shoals in the area that competitors were permitted to sail." (46)

Now the report starts to look into what was actually happening on the boat. Team Vestas Wind was the last boat to get pulled together (47) due to changes in sponsorship. Sea trials began on August 19, and all boats had to be assembled in Alicante by September 8 for the in-port racing beginning on October 3 (48). For comparison, Team SCA had been launched in October 2013 (52), and had ten months of training.

TVB's ability to pull itself together so quickly is partially due to the crew's professional background. Skipper Chris Nicholson had 20 years of pro sailing experience, along with four VORs, six world championships, and much more (49). Among the crew, there were 14 previous VORs, most significantly with Camper.

The navigator, Wouter Verbraak, was highly qualified. He was part of the 2010-11 Barcelona World Race (double-handed) onboard Hugo Boss, and had competed in a couple of VOR campaigns as either navigator or co-navigator. Also, the guy has a master's degree in physics, "completed in Sydney with sea breezes as his thesis." (50)

As far as sailing together, the boat arrived in Alicante on its due date with "only a few hours to spare," (52) and hadn't seen anything more than 25 knots in all its training. However, they won Leg 0, a race from Alicante to Palma, Majorca that was meant to test all the systems and equipment. The boat and crew seemed in excellent shape.

The report then turns to look into the watch system. TVB raced with a crew of eight, which meant two watches of three crew, and either the skipper or navigator floating (55). Each watch was four hours long, and often the skipper or navigator would drive the last half hour of the watch so that the outgoing crew could brief the incoming crew.

Nicholson "did not profess to having a detailed knowledge of navigation and all the navigation systems available in the boat. Clearly with his round the world experience he had very good general navigation knowledge." (58) So he very clearly depended on his navigator, and if Verbraak was asleep, he was to be "woken whenever there were any questions about the boat's navigation or before crucial points in the race." This meant that Verbraak got used to sleeping in 45-minute power naps. (175)

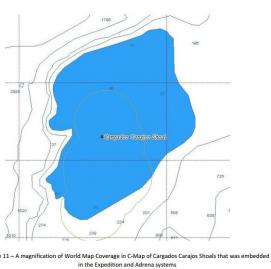

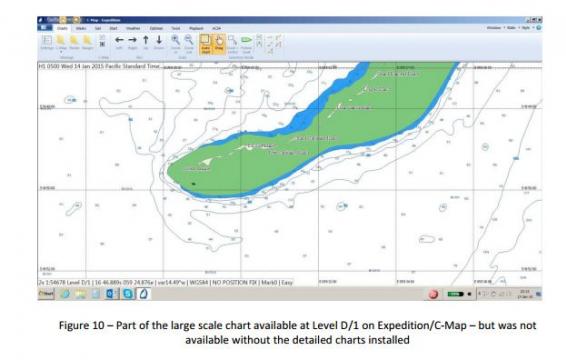

Onboard Vestas Wind, they had two laptop nav stations: one for weather and routing and the other for performance assessment and navigation. (62) The former ran Adrena software and World Map Coverage of the entire world at a small scale. The latter ran Expedition software. Several VOR crews complained that they had to be careful about overburdening the computers and crashing the systems. The systems were considered good, but not the best.

With the shakeup of the EAEZ, crews had a dramatically different racing area. "The change was significant, and although a forewarning was provided, several boats complained that a lot of their pre-planning was wasted and no longer relevant to the course being sailed." (66) In addition, crews set out from Cape Town in a tropical depression with winds of 35 knots, much higher than TVB had experienced on their boat. (67) This was, however, typical Cape of Good Hope weather and expected. Within eight days, the fleet had split into two packs, with TVB leading the second group. (68)

At least two days before reaching the area, Nicholson and Verbraak discussed the shoals and noted that they would likely pass very near to them. (69) This leads to what they saw on their electronic charts: the shoals "were investigated and determined incorrectly to be a 40m seamount. At different times, the navigator zoomed in on the electronic chart and came to the same incorrect conclusion." It's unclear which computer he was zooming in on, as he said he utilized both. (70)

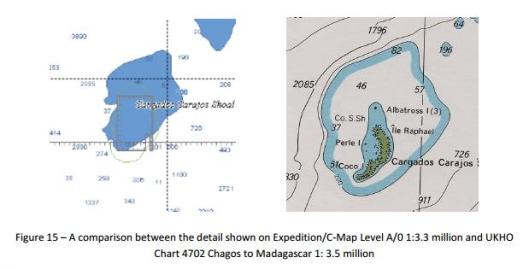

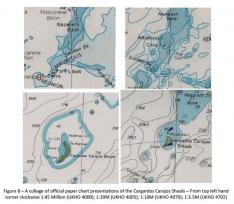

Different representations of the shoals, using both software and paper charts.

Within the rest of the fleet, "most navigators said they were alerted to the danger by the 'chart bounds' or 'caution areas and limits' overlays on the Expedition software, but they were generally surprised to find the detail at the higher levels of zoom with reefs, islands, and many dangers to navigation were not marked at all on the smaller scales." (119)

The tropical depression was now becoming more significant, and Nicholson was looking at steep seas, depth, and current to find a safe passage for the boat (71). He was told that the sea state would be monitored as they got closer to the shoals, that the depth was 40 meters, and that the current was negligible. Verbraak would have had to use both computers at the nav station to answer his questions fully, and it's unclear which computer he used to check the depth.

Another boat in the fleet purposefully passed very close to the tip of the shoals, and Nicholson and Verbraak looked at their track and decided they were "happy to sail over the Cargados Carajos Shoals that they thought, wrongly, to have a minimum charter depth of at least 40 meters." (74)

Verbraak was off watch, so he was sleeping. Nicholson was on deck, reefing the boat as she sailed through some heavy rain squalls at 12-16 knots. About 10 minutes before the grounding, the crew reported a change in the sea state and some disturbance ahead in the water, which they thought might be due to moonlight (the sun set at 6:21 p.m. local time). The crew was on deck, "peering into the night to investigate, when there was a sharp crack, which was the dagger board breaking." Rocks were sighted to starboard. The crew immediately furled the sails, depowered the boat, and canted the keel to port. The keel bulb had caught on a rock pinnacle, though, and caused the boat to pivot to port sharply, turning through 50 degrees in about 10 seconds. (78)

What follows is any sailor's nightmare. Two-meter waves were breaking over the boat's bow. The keel bulb was lodged in a gutter of the shoal, pointing the boat on a southwest heading and pointing to sea. This meant that the keel was on the wrong side, and the pressure from the sails was jamming the keel onto the reef. (81) "A couple of attempts were made to cant the boat up and over with the keel mechanism to get the bulb on the right side. This did not work. The situation was dire." (82)

The crew got the sails under control and called Race Control within six minutes of the grounding, as well as the local coast guard and a fishing vessel. Alvimedica was 50 nm away, and said they would be in the area by midnight to standby. The motion of the boat was "very violent and jarring," and the crew were having enough trouble just trying to hang on. No assistance was coming that night: they had to hang on until the morning. In a phone conversation to shore manager Neil Cox, Nicholson summed it up: "we're on a reef, we're not getting off, we're %&#ed."(84)

The crew got into their survival suits and tried to assess how they would be able to safely leave the boat. One crew member remained on deck, calling waves, while the rest of the crew stayed belowdeck in the cabin, where it was relatively dry and the main communications systems were still working (88). However, the boat was pitching and rolling in the seas, and the crew were being thrown about violently (89).

Around 10 p.m. local time, the starboard side of the hull was breached and the crew had to move on deck. Race control reported the cessation of telemetry data at 10:56 p.m., and the crew were limited to handheld VHF radios and mobile sat phones. (91)

The crew had already lost a lot of gear, including anchors, emergency water, and spare first aid supplies, when the bottom of the boat was damaged. The keel bulb broke off about two hours before dawn, and the boat began to roll even more than before. By this point, the boat "was nearly hard against the reef face and it would only require a good well-timed jimp to be on the reef and in relative safety." (96) The crew made the decision to abandon ship at roughly 3 a.m.

The crew managed to get on the reef, passing essentials, and Nicholson was the last to leave the boat. (100) By 3:15, all crew members were safe in their liferafts with no injuries other than a few bruises and minor abrasions. The crew set out to find Alvimedica, but soon decided to wait for the local coast guard. They were collected around 5:30 a.m. and transported to the Ile du Sud coast guard station to consider their options. Over the next two days they made trips back and forth from the boat, retrieving as much as they could and minimizing any environmental risks. (106)

In determining why the boat ran aground, the report finds that the two contributing factors were:

1. deficient use of electronic charts and other navigational data and a failure to identify the potential danger, and

2. deficient cartography in presenting the navigational dangers on small and medium scale views on the electronic chart system in use.

The late formation of the crew, short prep time in Cape Town, the change in the SI, the amendment to the exclusion zone and racing area, the tropical depression, the "taxing routine" between Nicholson and Verbraak, and the lack of access to planning support after the start were all listed as secondary factors.

The biggest part of the problem comes down to passage planning. Verbraak was highly experienced and did a large amount of pre-planning during the previous stopover. TVB had a large resource of paper charts from the Camper campaign in the previous VOR, and he worked with Roger Badham, a meteorologist. However, this level of planning was less than the other boats had. "Most boats spent as many as six days working closely with the skipper and navigator in the departure port," and one boat estimated that they spent $250,000 on a pre-departure navigation specialist. (141)

Verbraak received advice about the change to the EAEZ at roughly 9 p.m. the night before the start, plotted it on his personal laptop, and noted the Cargados Carajos Shoals were now part of the racing area. After the start, he used the Expedition software to investigate part of the shoals, but he didn't zoom in far enough to see the "detailed large scale chart that includes a clear presentation of the reef." (145) Mostly concerned with weather and routing, he would have been using a computer that would not give him a clear representation of the dangers of the shoals.

The report goes on to state that yes, they should have had a depth sounder going in unknown areas, but they can understand why they wouldn't. And yes, the skipper-navigator relationship onboard the boat was possibly "not well-developed," and that sailing a 65-footer with only eight people might not be calling it "fully crewed." (173)

The difficult question comes when you ask what you could have done differently. When the crew sighted a disturbance in the water, could they have gybed the boat and avoided danger? "A planned gybe needs about five minutes of preparation to get additional crewmen on deck, and 30 minutes to final completion with the need to rearrange the stacked stores. A crash gybe risks shredding the FRO, breaking the battens in the main and in some circumstances, with high winds, breaking the rig." (171) So Nicholson would not have been ready to risk that, knowing what he knew about the area having a depth of 40 meters.

"The report team considers the cartography in this particular case to be deficient," (203) and states that it was not entirely on the navigator. However, they consider it "a mistake for TVB to fail to obtain a more-detailed chart license for the weather and routing laptop that ran the Adrena system." However, this isn't totally on TVB.

"The VOR is operating at the extreme end of the recreational boating spectrum...and the boats are sailing round the world passing through large swathes of ocean that are poorly surveyed. They need the best chart and navigation systems available. (214) The report team considers that VOR should use its influence and leverage in the yachting industry to encourage the development of one or more navigation systems - charts and software - to meet the needs of professional racing. (215)"

And, personally, as an editorial note here, I'm fine with the idea of crews having Internet access so they can use Google Earth. I mean, really. It's not like they're going to be trolling ex-girlfriends on Facebook while they're out in the open ocean.

Read the whole report. It's fascinating.