The Most Common Causes of Boating Accidents, and How to Avoid Them

Brad Stemcosky has absorbed reams of eye-glazing boating safety material during the 30-some years that he’s been a weekend boater. But the lessons he learned from an unnerving brush with death on the water a few months ago have had a bigger impact: They’ve jolted him into re-thinking his whole approach to owning and operating a boat.

Launching his 15-foot fishing boat at a boat ramp near Piney Point, MD, Brad and a childhood buddy, Charlie Frend, were looking forward to an afternoon of fishing. It was an unusually warm day for mid-December, and although stormy weather had been forecast, it wasn’t expected to arrive until midnight—then 11 hours away.

That all changed abruptly near sunset, when the storm came sooner than predicted. The seas picked up, and the chop was replaced by mounting two-foot seas. Realizing the danger, the two men set course back for the boat ramp four miles away, but the heavier seas impeded them. Then, the bilge pump failed. The stern filled with water.

Suddenly a large wave capsized the small boat and flipped it over, dumping Brad and Charlie into the chilly 40-degree water. Swimming back to the turtled boat was more difficult than they expected. Although both men were wearing lifejackets, they’d left much of their survival gear onboard. Luckily, Brad was carrying a hand-held radio.

“It’s the longest second of your life,” Brad recalls, harking back to the moment they realized they’d just fallen in.

An hour and 20 minutes later, their Mayday calls so far unsuccessful, the two spotted a Maryland State Police helicopter flying over the water, and Brad—fingers numb by now—used his hand-held radio to give it another try. This time it worked. Minutes later, a local fire rescue boat picked them up and brought them back to shore.

For Brad, it was a lesson he’ll never forget—and he’s changed his boating habits to prepare himself better for emergencies. He’s begun keeping closer tabs on weather conditions and filing more detailed float plans with relatives, and he’s assembled a ditch bag filled with emergency gear, which he keeps ready to grab if his boat takes on water.

He’s also bought a personal locator beacon (PLB), which sends out distress signals to first responders if he falls into the water, and an extra hand-held VHF-FM marine radio that contains a Global Positioning System receiver and is equipped with Digital Selective Calling (DSC)—another form of emergency distress-signaling equipment.

“Wearing a lifejacket and having the radio—that’s what really saved our lives,” Brad asserts. “If we hadn’t been wearing the lifejackets, we never would have had time to put them on before we went overboard. Without a radio, we’d have been in the water for hours and gotten hypothermia. We would have died out there, no question about it.”

Stemcosky’s lucky escape says a lot about the importance of paying attention to the boating safety tips that the Coast Guard, the Maryland Natural Resources Police, local boating organizations, and magazines like this one send your way. For too many boaters, the messages go in one ear and out the other—until they’re actually in danger.

Not just beginners, but experienced mariners as well can unexpectedly get caught in serious situations that can lead to boat damage, injuries and deaths.

“I thought I knew a lot about boating safety before, but I didn’t take it seriously enough,” says Brad, who lives in Washington and works as a theatrical rigger. “You never think it’s going to happen to you. It’s always a story about somebody else. You don’t have time to read a manual when you’re out bobbing in the water.”

Based on interviews with boating safety experts, first responders, and veteran boaters, here are some of the safety lapses that most often get recreational boaters—including sailors—in trouble on the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries.

Impulsiveness

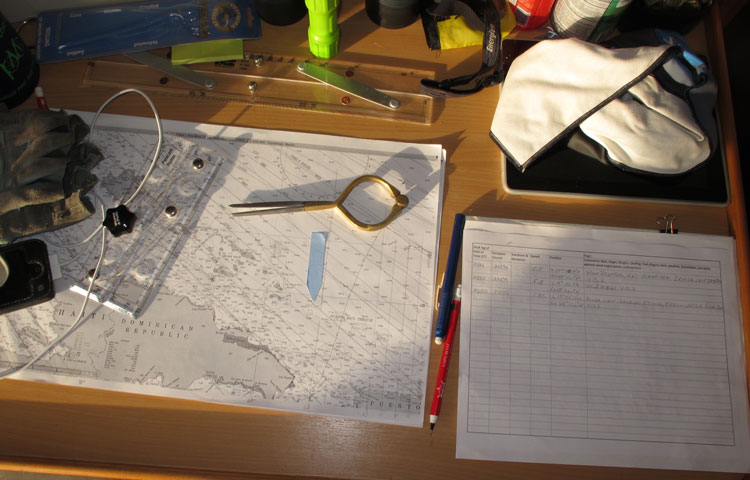

How much time do you spend on preparation before you get underway? Do you inspect your boat? Figure out how you’re going to leave the dock—and return? Prepare your lines and fenders? Study your chart to see where the channels, buoys, and shoals are? Test your lifejackets and safety gear? Check your fuel supply?

“Preparation is the most important word in boating,” says John McDevitt, a Coast Guard-licensed captain, marine surveyor, and boating safety expert. Even if you’re only going out for a few hours, you need to plan what you’re going to be doing and think about how to handle emergencies, McDevitt says. Bigger trips take still more planning.

Pride

Are you one of those sailors who boasts about going out in risky conditions? If so, it’s time you engaged in some hard-headed risk assessment before you go out. Will the weather be a threat? Is your boat equipped to handle the seas? Are you competent enough to handle this trip? How fit—and well-trained—is your crew?

Sometimes it’s important to scotch your plans and “just say no” if you aren’t sure you can handle your trip or cruise with the boat, crew, and conditions you face, says Alan Karpas, safety officer of the Chesapeake Area Professional Captains Association. “Being macho can get you in a lot of trouble,” Karpas says. “It’s too late then to reverse course.”

Defiance

You always fasten your seatbelt when you’re in an airliner or a car, so why are you so stubborn about wearing a lifejacket? As government statistics have shown and survivor Stemcosky has attested, you’re unlikely to have time to locate and don a life jacket once a boat begins sinking. Why not wear one all the time?

Until recently, you could sympathize with boaters who pleaded that the old-style lifejackets were too hot and too awkward, in the case of Type I jackets used offshore. But today’s inflatables are not only feather-light, they’re reliable, as long as you maintain them properly. Think of your lifejacket as a seatbelt. “Click it” before you shove off.

Neglect

As Stemcosky’s experience shows, the time to prepare for emergencies is before you get underway, not after they occur. And don’t stint. Buy more fire extinguishers than the Coast Guard suggests for your size boat (they empty quickly). Be sure you have a VHF-FM radio with DSC—and plenty of lifejackets.

And keep them all where you can get to them quickly without thinking twice. Coast Guard regulations say emergency equipment must be “readily accessible”—not stowed away in locked compartments or wrapped in plastic bags. Be sure your crewmembers and your guests know where they are and how to use them.

Mario Vittone, a former Coast Guard rescue swimmer now involved in boating safety activities, offers a simple rule of thumb for gauging how well you’ve equipped your vessel: “If you’re not prepared to be in the water, then you don’t have enough stuff on your boat.”

Indeed, safety experts say one of the reasons that first responders were able to rescue all 22 of the boaters who fell overboard when sudden gusts disrupted a sailboat race in mid-December was that all the sailors were wearing lifejackets and drysuits, had been trained in man-overboard procedures, and were prepared for the situation.

Intoxication

This isn’t on our list for propriety. Statistics show that even small amounts of alcohol dull the senses, impair judgment, and slow your response time. In Maryland, boating intoxicated is one of the top five causes of boating accidents. And it’s not just your crew. Even guests must be sober enough to function in an emergency.

Ignorance

You probably know a lot about automobile traffic rules—what a no-turns sign looks like, or when you’re required to turn on your headlights. But how well do you know the nautical Rules of the Road? Many boaters have never even looked at them, and some have misimpressions that can put them on a collision course with other boats.

Just listen to boater traffic on your marine radio, and you’ll find misunderstandings of the Rules are legion: Anglers assert that they have stand-on privileges that actually are granted only to commercial fishing vessels that are streaming nets. Powerboat skippers contend their larger boats have right-of-way because they’re bigger. Both are wrong.

Distraction

Jim Welday, a veteran boater who volunteers as a first responder, warns that many boating accidents occur simply because the helmsman isn’t looking where he’s going. Too often, he gets distracted, mesmerized by his chartplotter, setting the next waypoint, or fiddling with a piece of equipment. Suddenly, he’s in a collision.

By Captain Art Pine