Mark Wheeler went overboard in pitch darkness and a 40-knot squall.

This is the remarkable story of how his friends got him back.

SpinSheet covered this amazing story in 2017. Many thanks to Jeffrey Moag and the U.S. Coast Guard for this insightful video and recap.

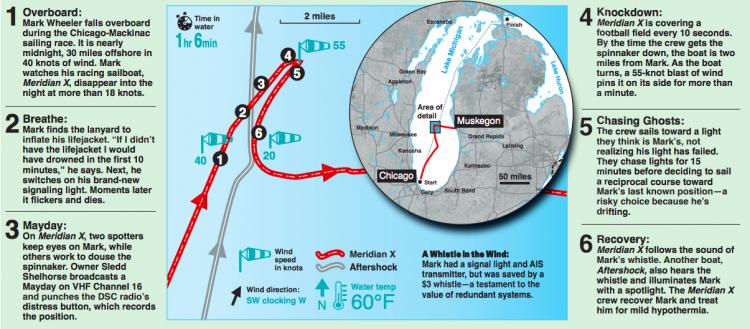

Mark Wheeler went overboard a few minutes before midnight. He was in the middle of Lake Michigan, 30 miles offshore in 40 knots of wind. As he fumbled for the lanyard to inflate his lifejacket he watched his racing sailboat, Meridian X, disappear into the night at more than 18 knots.

It was as if he’d fallen off the back of a powerboat running at three-quarters throttle, with one big difference. Meridian X was flying a massive spinnaker in a violent squall, and it was all helmsman Dave Flynn could do to keep the boat under control. Before the eight crewmen remaining on Meridian X could come back for Wheeler, they had to get that sail down.

“I knew it was going to be a long time before they were able to come back,” says Wheeler, 65. As a former F-14 Tomcat pilot with 30 years in commercial aviation, he was trained to remain calm in a crisis and focus on factors he could control. That meant one thing: staying alive.

“My job was to survive. If I didn’t do that, there’s nothing the guys on the boat could do to help me,” says Wheeler, who was competing in the 2017 Chicago Yacht Club Race to Mackinac, a 333-mile south-to-north traverse of Lake Michigan.

Wheeler’s first order of business was to keep his head above the waves and activate his inflatable lifejacket, which he’d set to manual so it wouldn’t fire off accidentally. He found the lanyard and inflated the lifejacket, then switched on a small light attached to the vest and held it aloft so the others “could see that I had gone through that first evolution successfully,” Wheeler says.

Next, he assessed his situation. He was 30 miles offshore, immersed in 60-degree water. The night was like pitch, moonless and storming. And his lifejacket wasn’t properly buckled. He’d been resting below decks when the all-hands call came to get the spinnaker down, and in the darkness and rush to get topside he hadn’t managed to secure the metal clasp. Now he crossed his arms over the two lobes of the lifejacket, and confronted a second problem: Minutes after he went overboard, his brand new light flickered and went out.

Wheeler had an Automatic Identification System (AIS) transmitter on his lifejacket, but knew Meridian X wasn’t equipped to track it. Also tethered to his lifejacket was an orange plastic whistle.

On Meridian X, two crewmembers had seen someone go overboard, but they didn’t know whom. “We literally had to do a head count to see who wasn't there,” Flynn says, “and once I find out who it is, I realize we’re missing the key cog in the wheel. Because to find somebody in the water, Mark would have been the most valuable person on the boat.”

Wheeler is an experienced offshore racer whose job on Meridian X is tactics and navigation. Under normal circumstances, he’d be the first to press the man-overboard button on the navigation system, and the best equipped to guide the vessel back to that location in total darkness and 40-knot winds.

To complicate matters, the crew was now shorthanded. Wheeler was in the water, and two sailors were assigned to do nothing but keep eyes on him. The boat’s normal complement of nine was effectively reduced to six.

The boat was still barreling downwind at a rate of about a mile every three minutes. Graham Garrenton estimates it covered two miles before the crew managed to douse the spinnaker. Now with the mainsail and smaller staysail still up, the 40-foot racing boat had to tack through the wind to start working its way back to Wheeler.

In the midst of this maneuver a 55-knot gust slammed Meridian X onto its side. The boat has more than 4,800 pounds of ballast in its keel to keep it upright under almost any circumstances. That’s why sailboats can heel at such crazy angles—like the children’s toy, they’re designed to wobble but not fall down. So a knockdown is an extraordinary event on a sailboat, and a hold-down—when the boat doesn’t immediately right itself—is even more uncommon. Garrenton estimates Meridian X was held down for about 90 seconds.

“A lot of us were hanging onto the lifelines and the toe rails with the boat almost at a 90-degree angle, trying to hold on until we could get the boat back on its feet and going the other way,” Garrenton says.

Through the chaos, the two spotters had kept eyes on what they thought was Wheeler’s light. In fact, when the strobe flickered out they’d confused it with a different light, probably on another boat in the Chicago-Mac fleet. Meridian X had gotten a superb start, and nearly 300 other vessels were spread out behind it in an arc some 30 miles wide and 40 miles deep. All of them carried lights, which appeared like pinpricks on the otherwise black horizon.

“We probably spent a good 15 minutes chasing lights that were just ghosts,” Flynn says.

Moments after Wheeler went overboard, skipper Sledd Shelhorse made a Mayday call on VHF Channel 16 and punched the emergency button on the DSC-equipped radio, marking Meridian X’s GPS coordinates. A few boats heard the call and stopped racing to aid in the search. Others had their hands full with the squall and didn’t hear the transmission. Still others confused the call with another emergency unfolding at the same time. A trimaran had capsized in the same squall that knocked Wheeler off Meridian X, and the Coast Guard had its hands full recovering the three sailors onboard.

When they realized they’d lost sight of Wheeler’s light, the crew decided to sail a reciprocal course toward his last position. It was the best strategy left to them, though not a perfect one. They knew Wheeler would drift—how far and in what direction was anyone’s guess—and precious seconds had ticked away before Shelhorse was able to mark his position. At the time, Meridian X was covering a football field every 10 seconds. The coordinates didn’t indicate Wheeler’s precise position; they were simply a place to start looking.

Meridian X motor-sailed on a reciprocal course, zigzagging a little to cover more ground. This was the hardest time, says Garrenton, “when you have time and space in your brain for all the thoughts to creep in.” The odds seemed impossibly long.

Then someone said he thought he heard a whistle.

Flynn was incredulous. “I said, you can’t hear a whistle out here. It's loud, it’s windy, stuff’s flapping and crashing and banging around.” But then another crewmember heard it. They knocked the motor back to idle. Now there was no mistake. Flynn steered toward the sound.

It was after midnight, nearly an hour since Wheeler had gone overboard. When he first went into the water he noted the position of a lightning storm to the northwest, using it to orient himself in the otherwise vast and featureless lake. Looking to the north he sighted a light, dim and low on the horizon. He blew the whistle with every breath. Slowly, the light grew brighter.

“When I saw that masthead light getting higher on the horizon and getting closer it was very encouraging, but also I knew this was going to be my one chance,” Wheeler says. “I just wailed on that whistle.”

As Meridian X approached from the north, another racing boat was coming from the south. The crew aboard the Farr 395 Aftershock had stopped racing to join the search. They too heard the whistle, and put a spotlight on Wheeler. The men on Meridian X maneuvered to recover their friend.

Flynn approached from downwind, easing the bow of the boat toward Wheeler as if picking up a mooring. “Once I was able to get my hands on Mark physically it was an overwhelming relief,” Garrenton says. “It was like a flood that just washed over the boat.”

The crew used a life sling to haul Wheeler over the stern. He was cold but not shivering, classic symptoms of early stage hypothermia. They got him below decks, wrapped him in blankets and plied him with warm drinks. Flynn steered for the nearest port, Muskegon, Mich., 34 miles to the east.

About two hours later Wheeler came on deck. Despite spending an hour and six minutes in the cold lake water, he required no medical attention. But as Wheeler said when his friends first hauled him aboard, he had survived a very close call.

Many factors contributed to his successful rescue, from his water-rescue training as a naval aviator to his ability to remain calm and focus on his job—staying alive and signaling rescuers by whatever means available to him, initially by activating his signal light, and after it failed, by using his whistle. The skill and persistence of the Meridian X crew was also essential to Wheeler’s rescue. They never lost focus, despite a cascade of what Flynn called “little disasters.”

If you’ve been reading closely you may have a mental checklist: Wheeler’s failure to buckle his lifejacket before coming on deck. The crew’s failure to activate the man-overboard module and immediately mark his position. Meridian X’s lack of an AIS transceiver to track Wheeler’s beacon (it was not required for the 2017 Chicago-Mac race, but is now).

Other factors were down to equipment failure, or just plain bad luck. A new light with new batteries flickered and failed. The Coast Guard had its hands full with another emergency. The squall that threw Wheeler off Meridian X, and then knocked the boat down, was not forecasted. Their luck wasn’t all bad. After the ignition key fell into the bilge when Meridian X was knocked down, one of the crew found it and the diesel fired on the first turn—no small thing, because as Flynn notes, “engines don’t like to start after a boat’s been heeled over.”

Wheeler and the Meridian team have learned plenty from the incident, and have adjusted their equipment and safety protocols. One of the most-important things is to practice man-overboard drills while shorthanded—just as they were when Wheeler fell off the bus. The team has a new boat (“Bigger and faster,” Wheeler says with a grin) and it’s equipped with AIS and redundant safety equipment, as is each crew member’s lifejacket.

The lesson isn’t to rely entirely on a whistle—in a perfect world Meridian X would have tracked straight back to Wheeler’s AIS position, and homed in on the signal light to pick him up. But one of those systems wasn’t available, and the other failed.

That simple whistle was the last line of defense, and it saved Mark Wheeler’s life.

Article by writer/editor Jeffrey Moag

For USCG safety tips click here.