In the third installment of our Safety Series, we look at the old adage, "Anything that can break, will."

Dean Benham, a longtime Chesapeake Bay boatyard manager, used to draw a chuckle from sailboat owners with his wry one-liner: “You ought to go sailing more often—and break something!” he’d say, as the customer left his office. The sailors, many of whom became his friends, invariably would grin and just shake their heads.

As everyone knew, Benham, a sailor himself, was only joking, not trying to scare up more repair business. But his wisecrack also was a reminder of how vulnerable to accidents a sailboat can be: an important factor for all of us to keep in mind. Benham’s point was simple: anything on a sailboat that can break eventually will, and you’d better be prepared to avoid it or cope with it.

There’s plenty of sailboat gear to put on the list of potential equipment failures: shackles, fittings, cleats, chainplates, shrouds, halyards, spars, winches, boomvangs, lifelines, hoses, clamps, seacocks, and a raft of others, even a mast. And it’s all under strain almost every time you go out.

“A sailboat is an accident waiting to happen,” says Michael Jewell, a Coast Guard-licensed captain who skippered his 40-foot sloop, Five O’Clock, to victory in the Maryland Governor’s Cup race last summer. “That’s why you need to take so much care to make sure she’s in good shape.”

Here’s a list of safety principles that are essential to all boaters—and especially for sailors:

Don’t stint on boat maintenance. Spend both the money and the time to make sure your equipment is in good condition and good working order. Test it regularly, preferably while your boat is still in the slip, but even while you’re under way. Don’t just assume that if it worked last week it’ll work again.

Train your crew in how to act in an emergency. Not only in the usual man-overboard drill. What if your roller-furler jams in heavy weather, leaving your jib flogging and dangerous? Suppose your transmission cable separates from the gear-shift lever, locking your boat in forward? What if you crack your knee on a cleat? Who’d sail back to port?

These are problems on all boats, but it’s especially critical on a sailboat, which is more complex and difficult to operate. Some sailors pride themselves on being able to “single-hand” their vessels—that is, sail it alone. That’s risky enough, but having a crew onboard won’t be a big benefit unless they know enough to be of use.

Planning is paramount. You can’t do enough of it, whether it’s scouring the weather forecasts or familiarizing yourself with the nautical charts you’ll be using. Do you have enough tools and spare parts on board to cover likely emergencies when you aren’t close to a boatyard? How’s your fuel? Water? Battery condition? Food?

Keep a sharp lookout always. It’s easy to get distracted if you’re fiddling with your chartplotter or even enjoying a conversation, but someone has to watch where the vessel is heading at all times, or you may find yourself in danger with no time to avert it. Two lookouts are better than one. Even experienced sailors sometimes miss things.

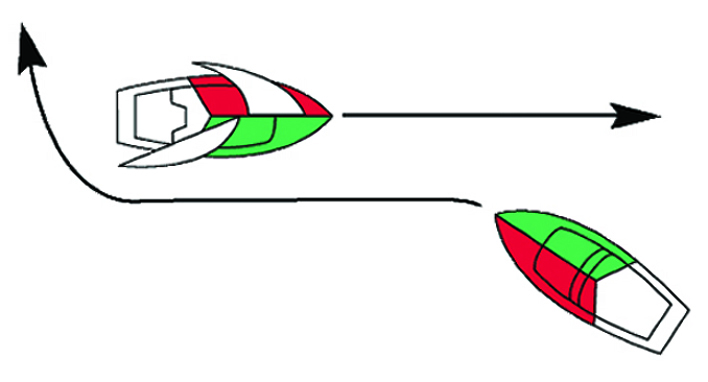

Rules of the Road. You may pride yourself on knowing the rules of the road pretty well, but what about other boaters? Don’t assume that those sharing the sea-lanes with you are familiar with how to behave on the water. Keep a close watch ahead and in all directions and get ready to act if danger seems imminent.

Yes, wear a lifejacket. You don’t have to tell that to dinghy sailors, but those who take out larger boats often ignore it unless the seas turn choppy. The point about lifejackets is they don’t do you much good in the water unless you’re wearing them, and when you actually need them, it’s usually too late to go hunt for them.

Brief your guests. Guests can be a lot of fun on a sailboat, but depending upon the size and layout of your vessel, they also can be a problem and sometimes a menace. Before you get under way, give them a flight-attendant-type briefing. Show where you keep lifejackets, fire extinguishers, and other safety equipment, and how to use the head.

Also warn them that a swinging boom resulting from an unintended gybe can kill; that it’s illegal to dangle your legs over the side; that they need to ask permission before they move around; that they should hold on to a grab rail or shroud when they go forward; that they should keep seated while you’re docking. (You probably have your own list.)

Avoid alcohol before and while you’re under way. Yes, it sounds prim, but studies have shown that alcohol dulls your judgment and response time and hastens the onset of hypothermia if you fall into the water. Sailboats are complex. Even passengers need to have their wits about them. Save that glass of wine until after you’re back in port.

Your VHF-FM marine radio. Remember that old credit card commercial? “The American Express Card. Don’t leave home without one”? In the case of VHF-FM marine radios, it’s “Don’t leave home without two”—a full-fledged bulkhead-mounted model and a handheld one to use as a backup.

And don’t forget to keep your radio on and tuned to channel 16 all the time you’re under way. Use it to check the weather (listen to the marine forecast at least once an hour), monitor distress calls and messages from other boats, and transmit when necessary. (Cellphones are no substitute. They only go to the party you’ve called.)

A boat is not a car. Sound simplistic? More appropriate as a warning for powerboaters? Maybe so, but some experts say ignoring that truism is one of the hidden causes of accidents that they witness on the water these days, even among skippers of sailboats.

You’ve probably seen this yourself, particularly with first-time boaters. The boat operator climbs into a 16-foot runabout, turns the key, and zooms off into the Bay. He has little or no training and no real appreciation of how water-borne vessels behave or what the rules of the road are. By the time he realizes he’s in trouble, it may be too late.

But it’s not just beginning boaters. Even experienced mariners can unconsciously revert to their car-driving habits if they don’t discipline themselves to think as mariners all the time they’re at the helm, says Chris Edmonston, president of the BoatU.S. Foundation, whose primary mission is promoting boating safety.

Now you can go out on the water and break something.