What to Know Before You Set Sail on the Intracoastal Waterway

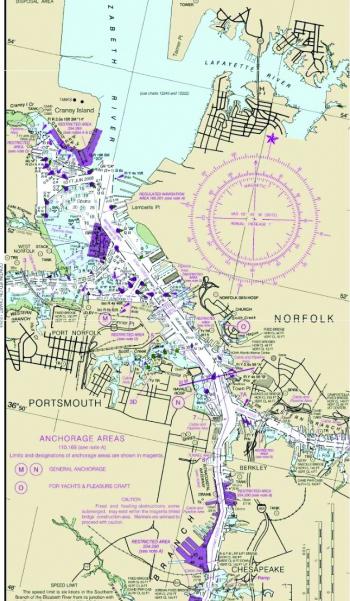

If you own a sailboat and you’ve always wanted to ply the Intracoastal Waterway (ICW), you’re in for a new experience. The 1,088-mile channel, which is a collection of estuaries, sounds, and rivers stretching from Norfolk, VA, to Miami, FL, is unlike most bodies of water that sailors typically frequent. It promises some unusual challenges, some satisfying, some not.

In broad terms, transiting the ICW needn’t be all that daunting. The waterway is protected and is a far cry from the challenges that ocean passage presents. There are plenty of marinas, boatyards, and waterside communities that together offer slip space, repairs, fuel, and other supplies, not to mention some interesting sightseeing and seaside communities to explore. Yet the waterway isn’t for beginners, or for boats that aren’t in A-1 shape before you start. Depending on where on the ICW you are, the water can be deep or so shallow that you may have to wait for rising tides. Currents can be very fast. You need to be able to read charts and day marks closely and to cope with heavy traffic. And you need plenty of patience.

For sailors, particularly, here are some points to ponder before you start making any serious plans: For all the attractions that the ICW offers, it’s essentially a big ditch. Except for brief sojourns on the Albermarle or Pamlico sounds—or an overnight escape into the Atlantic Ocean through one of a few widely separated inlets—there are few opportunities for you to raise sail and enjoy the wind. That means you’re going to have to spend the bulk of your time on the ICW motoring, which guarantees that you’ll be racking up a lot of engine hours, running the risk of needing extra maintenance and repairs, and spending two to three weeks motoring from Norfolk to Miami via the ICW instead of the week or so it might take to make the trip in blue water.

Parts of the ICW are silted-in and often unmarked, which leaves you more vulnerable to sudden grounding if you have a keelboat. Tide levels often are crucial. And navigation aids on the ICW sometimes are out of position, thanks to storms or shifting shoals. Dredging is imperfect. The “Magenta Line” said to mark a channel on chartplotters often isn’t accurate.

Sailors traveling the ICW also must cross under dozens of bridges and cables and through locks. Although charts show most of the bridges at 65 feet above the water at high tide, some spans don’t quite measure up, and a few are drawbridges that open only on regular schedules. Either way, you’ll need to factor all these into your planning and expect some delays.

That said, don’t be deterred. If you do take your sailboat down the ICW, you won’t be alone. Sailboats account for a hefty proportion of the recreational boats that travel the waterway each year, according to the Atlantic ICW Association. Many are captained by snowbirds, who head south in late fall to sail off Georgia and Florida.

“Don’t be afraid of it—it’s really one of the most beautiful waterways you’ve seen,” advises Paul Harmina, a Coast Guard-licensed captain who has transited the ICW frequently on boat-delivery jobs over the past 20 years and owns a 37-foot sloop that he sails for recreation. “If you make sure you’re prepared for it, the trip can really be a lot of fun.” Here are some tips for transiting the ICW, gathered from sailors who have done so frequently and from experts who keep track of what’s happening on the waterway: Stock up on information and charts. Buy full-sized (and up-to-date) NOAA charts of the ICW; updated electronic charts for your chartplotter; and a waterway guide that reproduces portions of nautical charts and lists ports, marinas, fuel docks, and restaurants along the way. Take a laptop or tablet and check the websites of several online ICW-monitoring organizations.

Learn the rules of the road—no fooling.

The ICW has a lot of traffic, from cargo ships, barges, and powerboats to sailboats and what-have-you, skippered by experienced boaters and newcomers alike. Especially in a narrow waterway such as this, you need to know the rules, from rules for meeting, crossing, and overtaking to requirements for lights and sound-signals.

Buy a good VHF-FM marine radio and one or two hand-held radios as backups.

And learn the proper procedures for using them (BoatU.S. offers a very good online course for $24.95 via boatus.org). You’ll need to use channels 16, 9, and 13 to communicate with other vessels and with bridges and marinas. Also bring along a laptop computer and a cell phone with a recharger or two and plenty of batteries.

Buy an unlimited towing insurance policy from an organization such as SeaTow or TowboatU.S.

If you break down or run aground on the ICW, it’s often difficult and expensive to get help if you aren’t signed up with one of those towing firms. Towboat captains also can provide updated information on local conditions.

Be sure your boat and everything on her is in tip-top condition...

...engine, electrical system, fresh water system, head, navigation system, anchoring gear, depthsounder, and seals and seacocks—and that you’re carrying enough parts to repair them if something goes awry. Even if you find a good boatyard, it may not be able to get the part you need for several days. Have a trusted mechanic go over your boat before you leave your home port. Check your batteries. Have everything serviced before you leave, from changing the oil and transmission fluid to installing a new impeller for your engine’s cooling system. Learn how to perform routine such tasks yourself.

Don’t box yourself in with a detailed plan for the entire voyage.

Sure, you should have a thorough grasp of the route you’re taking and what’s in store. But you’ll still have to spend evenings deciding what you’ll be doing the next day and checking the weather, potential hazards, navigation aids, marinas, fuel and food stops, and the like. Treat each day as a long daytrip. Captain Harmina writes the information he’ll need for the next day on a whiteboar d and keeps it where it’s easily visible from the helm. He also advises calling ahead first thing in the morning for transient slip space at a marina close to the place you intend to be in late afternoon. Few boats are under way at night because it’s so hard to spot the hazards in the dark. “Always make a fallback plan in case you don’t make it as far as you planned to go at the end of your day on the water,” advises Captain Jeremy Hopkins, a Coast-Guard-licensed delivery captain who plies the ICW frequently. “Have alternative marinas, anchorages, and so on, picked out in advance and know whether they’ll have space for you.”

Make a daily check of some of the online websites that track problems on the ICW

And read the updates posted by fellow boaters reporting broken or misplaced navaids, silting, or other hazards.

Keep in touch with other ICW travelers via marine radio and at your marina.

Some may have long experience transiting the waterway and know the hazards. You may find some who have just come from areas where you’re planning to stop, and they’ll have fresh information. Crews from other recreational boats usually are friendly and eager to share.

When you’re actually under way on the ICW, concentrate!

Don’t try to navigate on autopilot or keep your eyes glued to your chartplotter, says Captain Hopkins. You’ll need to be on the lookout for navigation aids, other vessels, shoals, and barely visible obstructions, even dead trees. Maintain a slow speed, and be sure you don’t leave a big wake.

Follow the ICW’s courtesy protocol.

When meeting head on, boats pass port to port. Those preparing to overtake another vessel call on channel 16 to let her crew know in advance. Captains slow down when passing to avoid wake damage to the other boat. Once you’ve been passed, position yourself directly astern of the other boat to signal that she can speed up.

Don’t try to rush.

You’ll find transiting the ICW is a lot more enjoyable if you take your time and avoid trying to meet a deadline. As in long cruises of any kind, expect to be delayed by one of the myriad potential difficulties you may encounter, and be prepared to solve whatever problem comes up. Captain Harmina’s advice about the ICW is, try it—you’ll like it. “If you do it right,” he says, “you’ll come back home saying, ‘Wow—that was a lot easier than I thought.’ ”

By Captain Art Pine