When the water splashing on the hull is not the normal color, it might be due to an algae bloom.

When we shove off to enjoy the warming waters of the Chesapeake, there will be days when we plow through some oddly colored water. That funny color might be due to an algae bloom.

It usually unfolds like this: We start to realize something’s not quite right. Something’s out of kilter. We may not notice it right away because we’re focused on the important stuff: getting out on the water and decompressing from the work week. We’re hoping the engine starts as crew members remove sail covers, stow provisions, weigh tactics, and wait for the late-arriving crew to jump onboard. But it’s there in our subconscious. The oddness settles in after we motor out, set sails, open a beverage, and finally sit back to breathe. It’s then, when life slows down just enough so we can bear witness to the world, that it hits you. The water’s color is wrong.

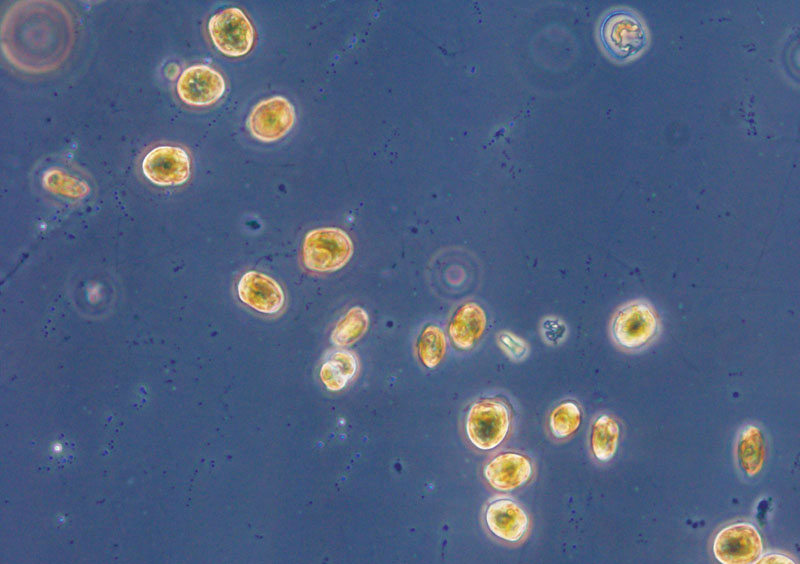

During the spring and summer, instead of green waters lazily splashing on the hull, we realize we’re sailing through an unsightly mix of browns, tans, oranges, and reds.

You might ask yourself, “Are we sailing through a sewage spill?”

By fall, there are long dark shadows snaking through the water like a prehistoric monster. The water reflects the color of Irish Breakfast Tea. What’s going on? It hasn’t rained in weeks, so it can’t be muddy runoff from a housing development… could it?

Nope. It’s not mud. The culprit is algae. You’re plowing through an algae bloom.

Algae are tiny aquatic photosynthesizing organisms that are an important part of the food chain. In the right balance, algae is good. Oysters, mussels, crabs, some fish, and a variety of other aquatic creatures depend on various types of algae for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Algae also use sunlight to produce oxygen that fish, crabs, and oysters all need to thrive.

Here’s the rub. Just like trees, vegetables, and flowers in May, algae also respond to longer days, abundant sunshine, warming waters, and nutrients, especially excessive levels of nitrogen. It’s the nitrogen that’s the problem. When it floods into waterways as a pollutant in stormwater runoff, nitrogen becomes junk food for algae. They explode in population.

This explosion creates what’s known as a harmful algae bloom. The one we typically track in local waters is called a Mahogany Tide. It turns our rivers orange/red because the algae that causes this, prorocenturm minimum, is itself red. Most of these Mahogany Tides occur in spring and summer, but increasingly our water quality monitoring teams with the Severn River Association are tracking other types of blooms well into the fall.

The problem with algae blooms

The problem with algae blooms is that they create “dead zones,” areas of water with very low levels of oxygen. This happens when the algae go through their life cycle. When they die, they sink to the bottom and decompose. It is their decomposition that depletes the oxygen. These “dead zones” accumulate in the bottom half of the water column (a process called eutrophication).

Note: The Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP) defines a “dead zone” as an area of water that contains less than two milligrams per liter (mg/L) of dissolved oxygen.

Fish, crabs and other organisms suffocate when they can’t escape these dead zones. On the Severn River, we’ve recorded cases where crabs and white perch suffocated when they were trapped in water that had less than two mg/L of dissolved oxygen. To thrive, rockfish need oxygen to exceed six mg/L. Oysters are happy campers when oxygen is greater than five mg/L. Crabs can tolerate oxygen as low as three mg/L.

The clarity of the water also drops precipitously due to algae activity. Rare are the days in summer when we can enjoy clarity of more than one meter. The CBP gives a failing grade to any clarity level that is less than 0.60 meters (roughly 23 inches). We frequently record clarity levels that are less than 0.50 meters. During algae blooms, we’ve recorded clarity as low as 0.12 meters (about four inches).

Underwater grasses wither and die

Algae blooms create havoc for our underwater grasses, which are invaluable to a waterway because they provide food and shelter for fish, crabs, oxygenate the water, protect shorelines, sequester carbon, and help clean the water by capturing sediment.

What happens if you try to grow tomatoes in a forest? No tomatoes. The same thing happens in the Chesapeake. The bloom blocks the sunlight from reaching a river bottom where the crucial grasses grow. Result: our grass beds fade away.

When osprey chicks go hungry

Our iconic raptor, the osprey, suffers because they only eat fish they catch in the Chesapeake and its tributaries, and they hunt by sight. Osprey do have great eyesight, but they can’t catch fish they can’t see. If an algae bloom lasts more than a day or two (in May of 2020 a Mahogany Tide persisted for nearly six weeks), the chicks can starve. The adults can survive periods of food insecurity, but the chicks cannot.

One thing homeowners can do to prevent algae blooms is to stop using lawn fertilizers in the spring. Sod experts report that most of the nitrogen in lawn fertilizer washes off a lawn and ends up in the river to fuel the next algae bloom. It’s also unnecessary. Sod experts say the only time your lawn may need fertilizing is in the fall when grasses turn that energy into creating stronger root systems.

by Thomas Guay

About the Author: Tom Guay runs the water-quality monitoring, floating classroom, and Operation Osprey programs for the Severn River Association. He is also a musicianer for the Eastport Oyster Boys and author of the historical novel, "Chesapeake Bound," due out with McBooks Press soon.